Regular readers will know that I am here on Substack after a long - very long - absence from publishing. My last few posts have been recent work - some of it published the day I wrote it - but I am also dipping selectively into my back catalogue.

As I write those words it occurs to me to wonder why I’m doing that, and I think, maybe, it’s a bit like suturing a wound. The 22 years since I ceased publication have been rich and fulfilling - raising beautiful children and growing a new love from seedling to what is now a beautiful intricate tree - but who I am now is also who I was then, and I feel a need to mesh the two halves of my life together again, more tightly.

My writing has always been how I made sense of the world, and myself, to myself, so what I am doing here is weaving old and new strands together to create a whole.

For the Mariners out there - I’m splicing a rope, one end tied to the bollard of my past and the other to my little boat of now, floating always on that interface of what was and what perhaps will be.

The poem below is part of that past. It happened to win the Bruce Dawe National Poetry Prize in the year 2000. For readers overseas, and probably for most Australians too, that may mean very little, but Bruce Dawe was one of Australia’s most famous and influential Poets and also a particularly lovely man, and in the small world of Oz Poetry winning Bruce’s poetry prize was an honour.

It was certainly an honour I did not expect. When the call came through from the Professor of English at the University of Southern Queensland (which hosts the Award) I was excited beyond belief. It was a work day, and my day job was decidedly un-Poetic. When my boss asked me what the prize would be I said:

“An all expenses paid trip to Toowoomba and dinner with a bloke named Bruce.”

(You probably have to be an Aussie to find that funny, but I laughed at myself all day)

Anyway…. I wrote Lajamanu Morning to help me make sense of my years living here - the little desert community of Lajamanu, in Australia’s Northern Territory, home to the Warlpiri Aboriginal First Nation owners of the Tanami Desert.

Photo above: Lajamanu - view from the mail plane, looking South into the Tanami.

Before we get to the poem, I probably need to explain a little more for readers who know less about Australia and the original owners of this land. A full explanation would be book length, but here is the best summary I can give.

The Aboriginal peoples of the lands now known as “Australia” have unbroken cultural traditions going back - well, they would say since the land itself was created. Archeologists and Genetic scientists have pushed the date for their arrival here to at least 50,000 years ago, and probably more like 65,000 years which, in human terms, is close enough to forever.

Over that vast gulf of time extremely stable societies developed, with around 250 - 300 language groups and many more dialects. Then - from the beginning of the European invasion in 1788 - they suffered the disruption and devastation experienced by so many First Nation peoples. In the remote desert lands of Central Australia the worst of that impact was delayed until well into the 20th century, but the same pattern was repeated. Disease, massacres (see my Poem “Junga Yimi” here on Substack), dispossession and forced labour.

The consequences are still being felt. Citizenship, land rights for some, and changes in public policy and attitudes, have been welcomed but the situation - particularly in remote communities - remains dire.

The Warlpiri people - living as nomads into the 1940’s and some later than that - now live in a scattering of small self managed communities in the Tanami Desert. They own their traditional lands, but incomes are very low, the climate is severe, health services are limited - as is housing - and food is incredibly expensive. It is also killing people.

The Warlpiri still hunt and gather - and the traditional foods are healthy - but the desert is a sparse table. To live off bush food you have to be a nomad, following the seasons and the game and the scarce water and never staying anywhere for long. Now established in fixed communities, people depend on the community store for the bulk of their food, but the nearest town of supply is almost 600 kms away (360 miles). The nearest city is 900 kms away (540 miles). Most of the food has actually come by truck from 2,000 kms away (1,200 miles) - the last of the journey over difficult roads. The freight costs are crazily high and perishable food - when it gets that far - is both expensive and close to expiry.

So now, people with a metabolism adapted over millennia to a low fat/low salt/low sugar diet are exposed to the opposite: tinned and frozen foods high in salt, sugar, fat….. The result: soaring rates of Diabetes, Kidney disease, Heart disease - and an average life expectancy far below the national average.

Despite this, the Warlpiri maintain a bright, vibrant, rich and creative society which overflows with life - family, ceremony, land, art, music, and laughter too. (The same applies to Aboriginal/First Nation peoples across Australia. I don’t mean to exclude anyone, but my poem is a specific observation about a specific place.)

In my years living in the desert I learned a great deal about life, from wonderful Teachers. I tried to give help back in other ways myself and I had - and still have - passionate views about the need to work in genuine partnership and dialogue with the original owners of this land.

When I finally left the desert, for family reasons, that leaving was a deep grief. I already had a body of Poetry written in the desert, to make sense of my experiences, and I added more - eventually published together in a slim volume (“Spinifex” - Five Islands Press, 2001) but I assume impossible to obtain these days.

Lajamanu Morning - like my other desert poems - is written from my viewpoint as a guest co-worker and observer. I can’t tell you what it feels like to be Warlpiri, but I can tell you what it sounds, and looks and feels like to be in the midst of their communities, under a hot desert sun, listening to the voices and loving the life around me while raging at my own inability to fix problems of racism, economic poverty and related ill health.

As with the note to my other poem published here (“Kngwarreye”) please do not think that I romanticise economic poverty, ill health and hardship - they are real, relentless and heart breaking.

I do hope, however, that the Poem recognises and conveys to you, the reader, some of the life force, vitality and generosity I had the privilege of experiencing in that small village which, at first, seemed to be in the middle of nowhere but, over time, I came to realise was actually at the centre of everywhere.

Photo below: Outside Lajamanu Store, loading up the Council truck with a few families for a 600 km/360 mile drive across the desert to Yuendumu.

The place is Lajamanu. The year is 1986. It is Summer, a hot wind blowing out of the desert to the South. The time is 10 am, and the Lajamanu Store is opening. Come inside with me.

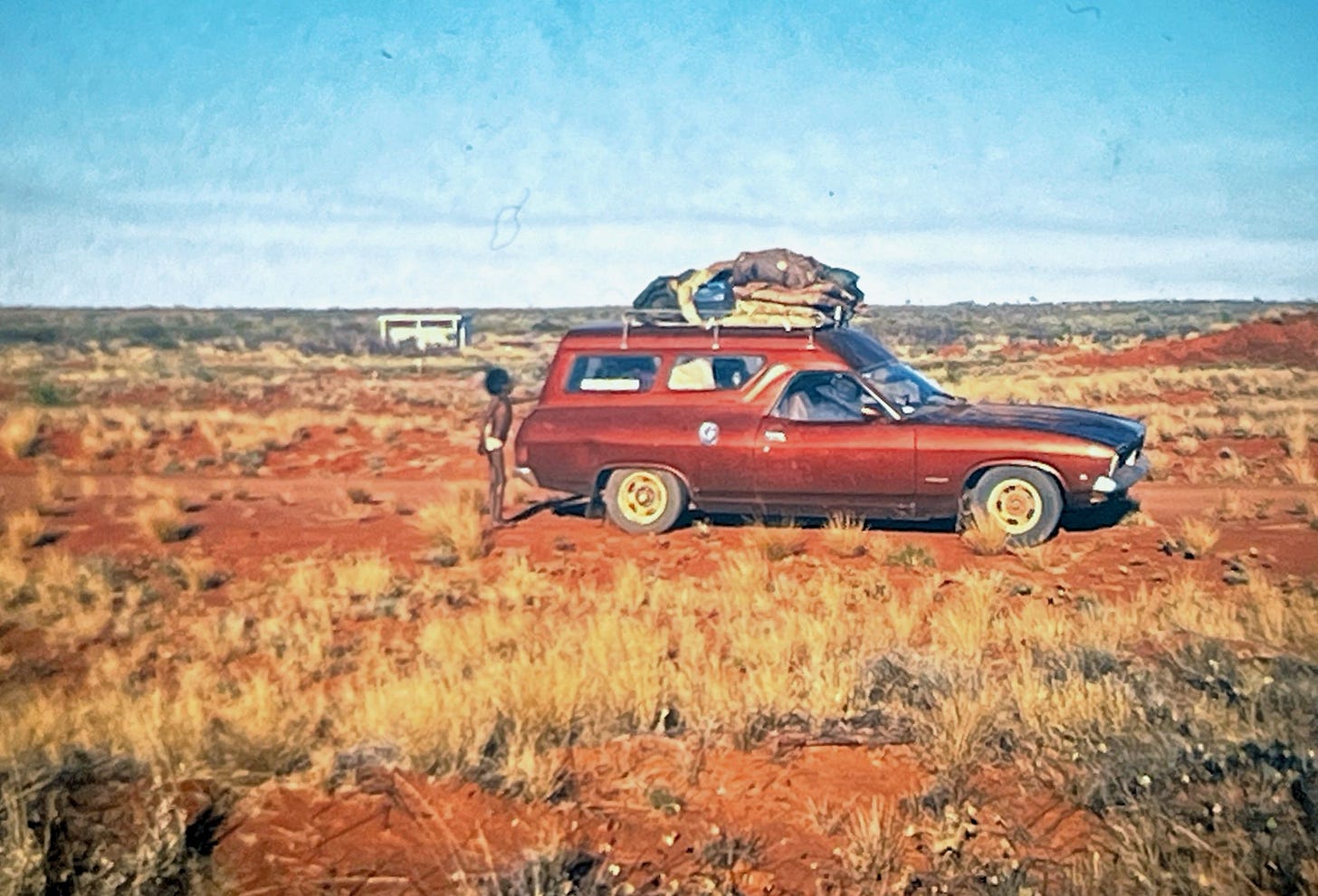

Above: My Ford Falcon XB panel van - heavily loaded - stopped at Jarnami Outstation in the central Tanami desert, half way on a journey from Lajamanu to Yuendumu - Central Tanami Desert.

Vocabulary:

“Kardiya” - Warlpiri for Europeans/non-Warlpiri. Literally pale or white/deathly.

“Business” - the English word commonly used as a short hand term for traditional ceremony. Sometimes expressed as “Men’s business” or “Women’s business” to denote gender specific cultural ceremonies, but far far richer and more complicated than the English term implies. A range of Warlpiri language terms apply.

“Business Camp” - a place and time of gathering for ceremony. In this instance, people were getting ready for the annual initiation ceremonies for the young boys/becoming men. (See my poem “Junga Yimi”).

“Tea Cosies” - just my attempt at describing the thick wool hats favoured by many of the older women. They are not really tea cosies - but they sure like like they are.

“Digging Stick” - I could have used the Warlpiri language word (“kana”) but that would mean nothing to non-Warlpiri speakers. Iron hard wooden sticks used for digging up yams/root vegetables; lizards; snakes and other game animals which hide underground. Also used in ceremony and for fighting.

“leather dogs” - the harsh living conditions impact the community dogs as much or worse than the people. Food is inadequate for everyone, let alone pets, and there is no such thing as a Vet. Dogs - hunting companions and pets - get sick with a range of illnesses preventable with the right treatments but unobtainable out bush. Many lose their fur.

“Infections” - you will understand the term, but you need to know the context. Inadequate housing and sanitation a hot, dusty, windy climate cause chronic eye, nose, ear and throat infections - particularly in children.

“Yuendumu” - the largest Warlpiri community - 600km/360 miles of tough desert roads South and East of Lajamanu.

“Land Council” - Aboriginal controlled Land Council - a body established to help coordinate land management in areas where traditional land ownership has been recognised under European/Australian law.

Journey’s end - camped at Yuendumu.

All photos: Me.

Poor image quality: Deliberately Me. These are old slides/transparencies. I could get the tech to produce sharp images, but I don’t want to show images of Warlpiri friends who might then be recognisable. Three reasons: culturally, images of people who have died are not generally acceptable, and I don’t have their permission anyway. Besides - this is deep memory. This is the washed out water colour that seeps into us, and makes us who we are.

When I dream though, it is as vivid as today.

One long sentence! Very vivid, David! To use a photographic term, like captured with fisheye lens.

Oh wow, this is incredible - the imagery, the form, the breathlessness, the unrelenting thrum of language, desperation, sun. I will be reading and rereading this. Thank you for sharing it with us here.